As a child, my beloved grandmother told me lots of stories. As she was a New Zealander, this included lots of references to Maori culture. From a young age, although she was Pākehā white woman herself, she was taught a great reverence and respect for Maori traditions, music and stories.

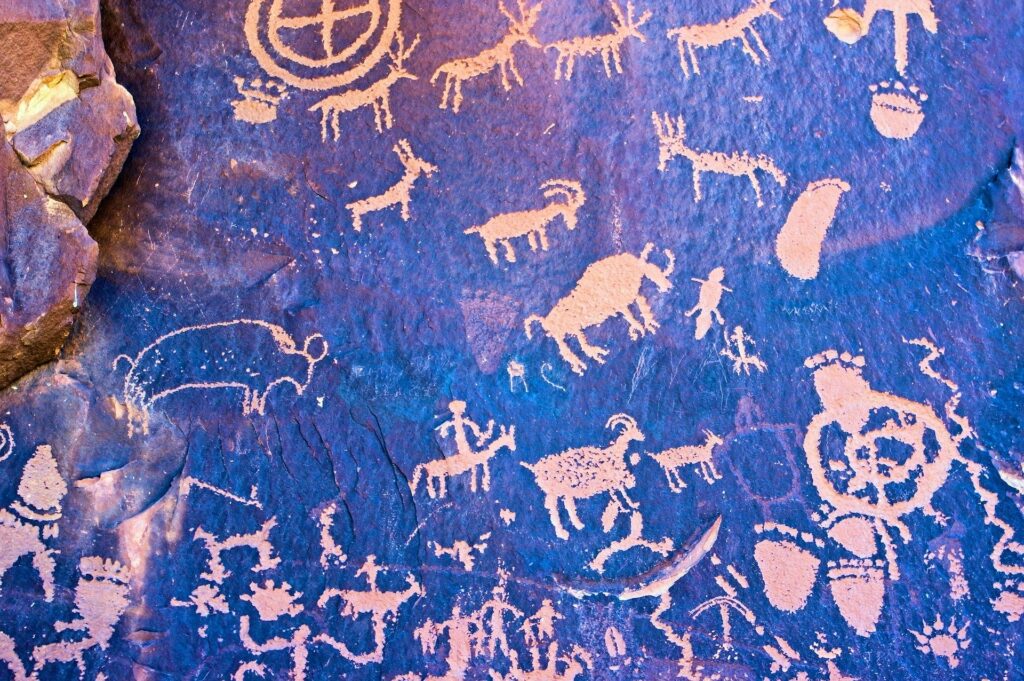

Whether in Canada, the USA, Australia or New Zealand, the history of indigenous or First Nations people have been sadly shaped by many shocking examples of exclusion, prejudice and discrimination. However, it is also important to learn about and celebrate the things we can learn from these cultures which value their elders, the continuity of story from generation to generation and the pride and resilience of people to stand tall, even when others label or stereotype them.

Sue Olsen, a Canadian friend of mine tells me; “Storytelling or oral history was always a part of my life growing up. I always knew where I came from and who my people were. It is important to me as it gave me direction and my identity, I am proud to be a Metis woman.”

Sue told me about a book written by a scientist during International Polar Year, entitled ‘Two Ways of Knowing – Merging Science and Traditional Knowledge.’ As the title suggests, it gives weight to traditional knowledge, to the stories that help contemporary scientists understand, in this case, northern climates and northern people, that the elders who pass on the stories matter, it is understood to be relevant in today’s society.

There are important messages here when we think about how we give more weight to medical knowledge sometimes in traditional health and social care assessments. When I used to attend multi-disciplinary meetings about a particular person with dementia, it always struck me that everyone listened the most to the psychiatrist who had perhaps only spent half an hour with the person. The people in the room who knew most about the situation – the person themselves, their relative and possibly a care worker who had known them for years, were not given nearly as much regard or attention. Yet they were the ones who really knew the intricacies of the story of that person, to help give the very best support.

Interestingly, First Nations storytelling focuses not just on words, but on intonation, vocal and body expressions, pace and all the things to which we need to pay close attention in relating to a person with cognitive impairments. As Archibald (1997, p.10) said, “Patience and trust are essential for preparing to listen to stories. Listening involves more than just using the auditory sense. Listening encompasses visualizing the characters and their actions and letting the emotions surface. Some say we should listen with three ears: two on our head and one in our heart.”

The telling of stories has long been associated with strengthening identity and belonging. In Aboriginal cultures, stories of healing can be of particular value as they provide hope and show that healing is possible via a multitude of different pathways. The ‘Dreamtime’ is the Aboriginal understanding of the world, its creation and its great stories.

When we think about coming to truly ‘know’ a person we are supporting, how often do we ask the question; “What are the stories in your life which are important to you? What are the stories you would like me to hold dear and continue for you?”

When my grandmother was dying in hospital, she gave me her gold charm bracelet that had many charms which had been given to her over about 50 years by special people in her life. There were giraffes and elephants from Kenya where she had spent time, a Maori ‘hei-tiki’ made from pounamu and many other treasured gifts. I will never forget her quietly talking me through the story of each charm. She was very weak, but determined to share each one with me. She was literally and metaphorically handing me her story because she trusted me to take care of it for her once she was gone.

Not everyone has somebody in their life who will be there for them near the end of their lives to honour their story. But everyone of us who supports a person in need can learn to listen with our heart as well as our ears, know that each and every story has meaning and significance and deserves to be witnessed.

References and further reading:

Archibald,

Archibald, J. (1997). Coyote learns to make a storybasket: The place of First Nations stories in education. Simon Fraser University dissertation

https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/stories/index-e.html

Aboriginal storytelling